Thank You for Your Service

Veterans in the Parking Industry

There are a lot of veterans in the United States—16,501,502 as of 2021 to be exact. Whether serving for 20 plus years or for a single enlistment, veterans have been through experiences that civilians have not and would struggle to understand. We interviewed five veterans from the parking industry in various roles and found five common threads regardless of time spent in service, rank, military branch, or role. Civilians reading this article will certainly find valuable insights that will help in working with and managing veterans—and veterans reading this will find themselves in turn chuckling and nodding their heads in understanding.

#1: Structure and Cohesiveness

One of the great strengths of the military is its core structure and the trust and cohesion it builds between superiors, subordinates, and peers alike. It ensures that teams are aligned and know how to achieve goals; this is an essential trait of a high performing team, but often elusive in the civilian world. Veterans have had to learn how this works the hard way, and are able to lead, follow, and contribute effectively in structured environments.

Senior Chief Petty Officer Rome Ring (Ret.) says the clear definition and instruction given to all things, with manuals covering every topic from armored vehicle repairs to how to make your bed to mopping a floor, allows for a common understanding of shared tasks and how to perform them. This builds what the military calls “unit cohesion.” That level of cohesion was also brought up by Petty Officer 3rd Class Tracey Guillon, who said that the central idea is that you are only as strong as your weakest link, which gives everyone a higher incentive to work together.

Ring also says that learning how to organize like the military does give you a competitive advantage. Learning to drop supplies on a beach and turn it into an airstrip in two hours or takes some serious organizational skills and teamwork!

Petty Officer 1st Class James Gibson (Ret.) recounted that his commanding officer was well known for holding all service members under his command to the same standard, regardless of rank, and punished all infractions equally. This approach to “good order and discipline” is largely lacking in the civilian world, which can at times prevent the building of a unified and efficient team.

#2: Mental Toughness

Specialist Richard Berlanga commented that building the foundation of mental toughness is essential to overcoming larger tasks, like your first twelve-mile road march while carrying a full load of gear on your back. In this example the real test isn’t physical, it’s mental; are you a quitter, or will you push yourself past your limits to complete the mission? Sometimes the situations that require a hardened mental approach are less of a “test” and venture into the strange, trying, or just outright outlandish. Berlanga also talked about traveling by helicopter when it was targeted by a missile’s guidance system—a normal reaction would be panic. Instead, he joked about the occurrence and said that during this event he simply began to wonder, “Maybe I shouldn’t re-enlist?”

Gibson pointed out, “What they do in the military is life and death—you want to make it home to see your family, you have to follow the rules and pull your weight.” This is an absolute fact. Even in peacetime or non-combat areas, military life can be dangerous. Training accidents happen, and there is an inherent risk in everything you do when you train for conflict. These environments require constant focus, attention to detail, and the mental discipline to maintain both non-stop over sometimes extremely long periods of time.

In the military, the process of skill mastery is very linear; not doing so is not an option, so a skill is mastered and then you move on to the next one. The patience, persistence, and ability to get results without giving up because something is too difficult is something veterans excel at.

#3: Inclusivity

The United States is often referred to as a “melting pot”, and the U.S. military is a true representation as it is composed of all types of individuals from all of its states and territories. These individuals are taken, trained, and ultimately stationed together with no regard for place of birth, upbringing, religious beliefs, race, etc.

The true core of what builds the unbreakable and lifelong bonds between service members are the sacrifices made for one another whether it be in time, sweat, or otherwise. Veterans will be core members of teams and organizations that successfully include all team members to navigate adversity and will be dependable, steadfast, and determined.

#4: Applying Skills to the Civilian World

After leaving active service, many veterans find that their skill sets don’t easily apply to civilian roles. They often have trouble translating their military experience in a way that is relatable and correctly conveys the right message to a civilian employer. Many roles in the military require learning a skill set that ultimately leads to some level of destructive capability clearly not needed outside of that environment. What civilian employer would find a need for an individual who could retrofit a civilian 747 with high caliber machine guns and high explosives? Or maybe an individual who can navigate their way through a live minefield?

While the specifics of a skill may be difficult to parallel to the civilian world, what does apply are the base traits that allow service members to learn and master new roles and equipment, or how to “adapt and overcome” when not provided the correct tools for a job. Ring talked about the organizational skills he gained, “Learning how to organize like the military does can give you a competitive advantage.” Organization can be applied to physical inventory and equipment, but also to processes and people. Good organization of people can often equate to well-developed leadership skills, which in turn create highly efficient and motivated teams.

Often, veterans encounter difficulties finding ways to express what their skills can translate into in the civilian world. It is hard to accept that military certifications do not directly equate to a civilian equivalent. Frequently a veteran, fresh out of the military, will not understand how to attribute traits and abilities to skills in the civilian workplace. Working with live explosives? Try “detail oriented.” Proficient at launching aircraft rapidly from an aircraft carrier? How about “excellent communication skills.”

#5: Stereotypes

When most people imagine veterans, images of Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore from Apocalypse Now or Gunnery Sergeant Hartman from Full Metal Jacket often come to mind. While you may find those characters among real veterans, the truth often could not be further from the stereotype. Most service members do not operate in direct combat roles and instead perform a wide variety of tasks from repairing airplane engines to programming complex encryptions used for communication equipment. Frequently the first question asked of veterans by civilians is the dreaded, “Have you ever killed anybody?” Berlanga has commonly come across the assumption “that they’ve all been through battle and may have PTSD which is not always the case.” The actual truth is that only about 10% of service members will ever see combat, and the ratio is about 10 people needed to support every one infantryman on the front lines. Tucker stated, “People sometimes think you are a racist, redneck, gun toting extremist from rural America. But really everyone served together no matter what their background.” This highlights how far from the truth the first statement is. Ring even pointed out that he eventually stopped highlighting his military career of more than 20 years due to being stereotyped into security roles instead of IT where he wanted to work.

Our interview candidates all expressed a level of frustration with the idea that veterans are all killers, aggressive, crazy, or misguided. They simply want to be judged based on their own character and achievements.

Working With Veterans

Working with and managing veterans within your teams can be a challenge without understanding what makes them different. Ring described young veterans as being more receptive and dependable than their peers and requiring a lot less “babysitting.” He attributes that to their having already learned structure, accountability, and timeliness among other factors for success. Tucker also stated that veterans tend to be faster, more efficient, and better able to work in teams, and that these skills come pre-loaded with that veteran into the workplace.

All our interviewees agreed that they were much more easily able to connect and communicate with veteran employees due to the shared experiences and mindsets towards completing the end goal. Gibson did note, “Sometimes it is civilian non-verbal communications that cause veterans to shut down. I understand and relate to them. It can be tough, especially for people who have seen combat. Civilians can’t relate to these experiences.”

But as you can see, having veterans as part of your organization can give you an advantage; all you need to do is understand a little about them. And from all our interviewees: You should definitely hire more vets! ◆

Stephen Logan, CAPP, (CPL, US Army, Combat Medic) is an Operations Manager for LAZ Parking, Ltd.

-

This author does not have any more posts.

Brandy Stanley, CAPP, MBA, is Vice President at FLASH Parking and Co-Chair of the IPMI Sustainable Mobility Task Force.

-

Brandy Stanley, CAPP, MBAhttps://parking-mobility-magazine.org/author/brandy-stanley-capp-mba/July 6, 2022

-

Brandy Stanley, CAPP, MBAhttps://parking-mobility-magazine.org/author/brandy-stanley-capp-mba/April 6, 2023

-

Brandy Stanley, CAPP, MBAhttps://parking-mobility-magazine.org/author/brandy-stanley-capp-mba/April 2, 2024

![Sustainable Mobility Member logo_shutterstock_305262863 [Converted] Sustainable Mobility Task Force member](https://parking-mobility-magazine.org/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/Sustainable-Mobility-Member-logo_shutterstock_305262863-Converted-qi7xcj3bd8rwmc35safhmp022pw0j1nx5b6at8n9xg.png)

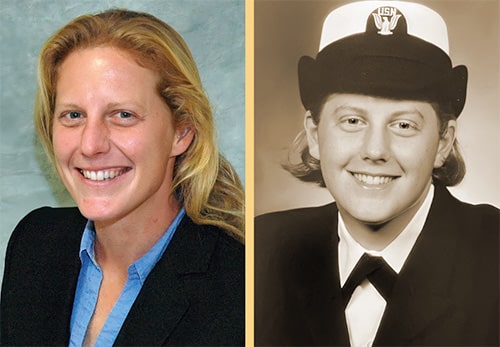

Who We Interviewed

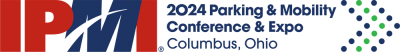

Rome Ring

Senior Director of Operations, LAZ Parking

SCPO, United States Navy, 20 years, 1 month service

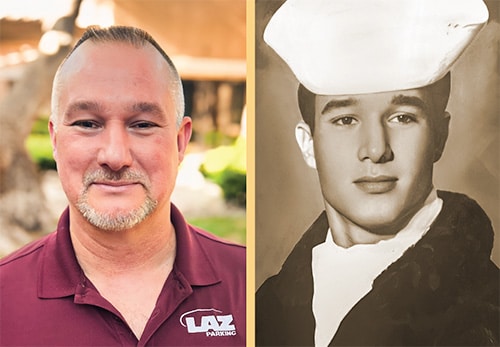

James Gibson

Parking Services Administrator, City of Las Vegas

PO1, United States Navy, 20 years

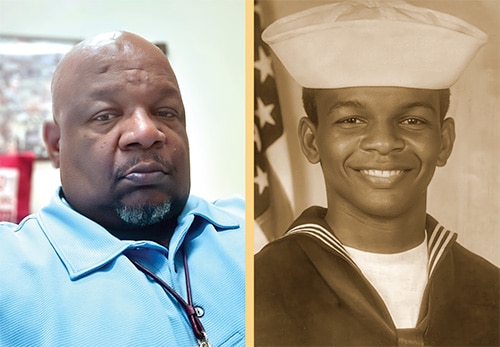

Todd Tucker

President, Parking Logix

LCpl, United States Marine Corps, Combat Engineer, 4 years

Tracey Gullion

Regional Auditor, LAZ Parking

PO3, United States Navy, CTR, 3 Years

Richard Berlanga

Senior VP, FLASH Parking

SPC, United States Army, Medic, 4 years

Stephen Logan

Operations Manager, LAZ Parking

CPL, United States Army, Medic, 7 Years

International Parking & Mobility Institute (IPMI) and Veterans in Parking (ViP) are strategic partners dedicated to get esteemed military veterans back to work by helping our members and allies in parking, mobility, and transportation post available positions and find qualified professionals to fill them. Find out more at Veterans in Parking (vetsinparking.com) or visit IPMI’s Career Center to see available postings.

Table of Contents

The Evolution of a Parking Professional

Everyone has an origin story. This is mine.

The Importance of Upskilling & Reskilling

In this age of technology and with the continued implementation

Positioning for Success

The Evolution of Parking & Mobility Profession.

The Importance of Upskilling & Reskilling

In this age of technology and with the continued implementation

The Evolution of a Parking Professional

Everyone has an origin story. This is mine.

Positioning for Success

The Evolution of Parking & Mobility Profession.