Lessons from a century of urban parking and planning practice.

A century of mass car production and planning for mass car parking has ultimately provided easy access to degraded places. As the car replaced the horse and urban transit, responsibility for the planning of mobility and parking in our cities and places has transferred from the urban-town planning profession to transport planning with important consequences for place and access.

The issue of professional practice is considered here as part of a series of discussions on the subject of “Rethinking Parking,” which also considers the issues of place, policy, politics, and pricing. Here, we discuss the issue of professional practice with a view to parking outcomes that also ensure we still have places worth visiting. This discussion considers the early urban planning focus on urban mobility balanced with quality of life in the city, the evolution of professional practice, and a way forward to improved urban place and parking outcomes. Unpacking our thinking about professional practice may enable a better balancing of the core needs of transport, parking, and place.

Cities and Places and Planning

Traditional cities are typically found on and around transport routes—rivers, roads and railways. They occupy strategic locations for trade, security, crossings, and meeting points. Streets/roads define the city/urban form as both paths and edges. In the past few centuries, attempts to fix the city have focused on the restructuring of the road and transport systems, note the making of the Paris boulevards, the radical vision of Le Corbusier, or the location of rail station terminals over ‘“slum” areas in London through to the creation of highways and freeways into the through our cities. New transport technologies have been central to the rethinking and reshaping of the city; that has been the case in the past and will very likely be the case in the future.

The idea of town or urban planning developed in the early twentieth century. Early planners were mainly drawn from the architecture or civil engineering professions supported by builders/developers and interested parties. The early idea of planning was mainly focused on solving the problem of the horse and its excrement making the city a dirty, smelly, dusty, and disease-ridden place. The horse and later, the horse-drawn tram shaped the form and function of the city. As the horse gave way to the automobile, it was reshaped again, initially by the reuse of barns and stables as garages and blacksmith shops rebadged as mechanics. Early cars were not weatherproof and required undercover storage. Maps of the early twentieth century show large stabling precincts around the wharves, warehouses, and at end of tram lines and rail stations. As horse and transit-drawn freight declined, many of those significant land areas evolved, with mass car ownership, into urban car parks and park and ride.

More cars led to improved roads and extended the city beyond the railway/tram routes and their suburban areas to new suburbs. The car and the suburbs attracted the affluent classes away from the city, but their employment, goods, and services were still located in the city.

A review of the media indicates that the problem of urban parking occurs across the board from the early 1920s. Mass car and mass parking became an intractable problem for urban planners, maybe because it had not occurred to them that they had to destroy their city. It is from about this period that we find the seeds of the early transport planning profession splitting from the urban planning profession. This can also be linked to the idea of modernism which underpins the shift to highly specialized, siloed strands of expertise. With this are bureaucratic structures with defined responsibilities and budgets.

Urban Planning and Transport Planning (and Parking)

The urban planning profession tends to see the car and the need for parking as a threat to the thousands of years of ideas that have shaped the traditional city. The car park is the antithesis to the beauty of the form and function of the traditional city, turning vibrant communities into blighted, vacuous landscapes. Even when parking is managed out of the way, its associated traffic increases congestion, noise, pollution, and subordinates pedestrians to third-rate citizens.

Even within transport planning, urban parking policy and delivery can be seen as marginal to the profession, it’s the Cinderella of transport planning jobs. These planning professionals are caught between the ideal of an objective transport planning practice and the subjective of city hall politics and emotional populism. Beyond the politics are the brutal economics where those concerned with developing quality urban parking/place outcomes are required to squeeze the maximum amount of parking out of the least amount of investment. There is little room for idealism here.

The seeds of professional planning to provide for parking might be traced back to the planning for places to accommodate horses and carts/carriages—access to limited curb space, zoning for the provision of off-street storage, rules for managing local amenity and pollution, etc. It was an extension of the urban planning challenge, at least to the extent that planning actually took place. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the automobile was only available to a privileged few who formed auto clubs, which were very effective vehicles for lobbying. These clubs engaged with decision-makers to influence decisions on transport expenditure. The right to easy, affordable car parking was one of the earliest campaigns successfully waged and won by auto clubs.

More cars and roads/freeways and parking demanded more specialized knowledge, and so the need for a dedicated transport planning profession developed. Computerization enabled complex transport modeling, which underpins the idea of an objective, science-based transport planning profession.

The idea of modernism accentuates the notion of specialization. Professions become increasingly closed and siloed. In the post-WWII period, the Department of Main Roads/Transport became the dominant influence in deciding the form and the function of the city. The notion of planning cities and places as a community-focused consult-and-decide practice gives way to a top down announce-and-defend form of autocratic governance. In this environment, decisions that enable car parking to continually cannibalize place ignore and damage affected communities, to serve a “greater need.”

There are clearly many efficiencies and achievements in this approach but there have been great costs. A century after we created the planning template for the planning and delivery of urban parking, there are significant new trends, challenges, and opportunities. These changes invite us to pause and consider if we can do better for the next century.

Integrated Planning Approach

Doing better, achieving “smart” urban parking outcomes can be seen as complex and maybe too hard to achieve via a siloed approach to planning. Maybe we need to rethink the process of planning and delivery of parking; maybe we need a more sophisticated planning approach, an integrated planning approach that is able to deliver complex, integrated planning outcomes.

Rethinking parking for the twenty-first century requires that we think beyond the professional siloes we have created. There is a need to integrate parking with a range of evolving policy areas and new challenges and opportunities. The extent of change will vary by place, but a helicopter view highlights a number of notable trends. These include the rise of AI (note how this may also radically improve urban transit options and reduce costs), electric vehicles, and provision of charging stations with parking, the booming car-share/ride-share economy, a decline in dependence on the private car, a concern to minimize climate change impacts and improve environmental outcomes, and rethinking cheap/free and expansive park-and-ride in favor of transit-oriented development.

There are new and affordable parking technologies that increase the efficiency of parking, such as ground pods that inform real-time signage and demand-responsive pricing. These innovations reduce some of the negatives of urban parking, including cruising and parking related congestion.

There are also changes to the governance around urban parking. Social media has increased the level of community activism and potentially improved the ability of government to engage.

Changes that affect professional practice include the move away from minimum rates parking policies, an increasingly critical view of modeling, including the questioning of opaque assumptions that underpin transport and parking models and established but questionable ideas such as predict and provide. It is even possible to argue there has been a shift in an ideology based on abstract modeling to consider more subjective place- and people-oriented solutions.

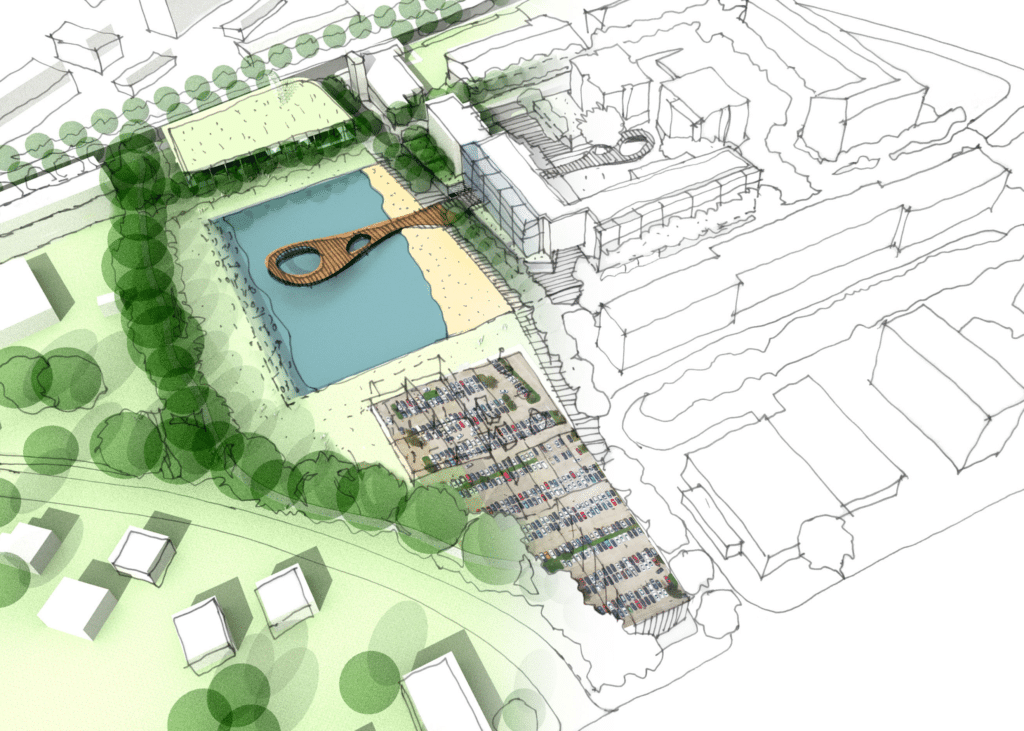

Many cities are seeing a revival of their inner urban areas, especially with gentrification and the rise of non-traditional economies. Middle class professionals moving into inner urban neighborhoods may be more connected into the decision-making processes that shape cities and places. This seems to be evident in the growing resistance to the cannibalism of the urban environment for easy, cheap parking, the concern for improved urban design, walkability, and places to spend time and money in. People want healthy places with greener streets with physically and visually permeable edges. There are concerns to improve the environmental performance of cities with more shade, water sensitive urban design. Overall, we are thinking more carefully and creatively about our inner urban places with a view to achieving higher and better land use outcomes than cheap, easy car storage.

There are many reasons to rethink parking and the professional practice that provides poor urban parking outcomes. There is a need to think more creatively about planning for parking and the idea of integrated planning to deliver smarter urban parking. The lessons for this are not so far away.

In the past few decades, transport and urban planners have had to collaborate to deliver urban transit/light rail projects. These are projects that go beyond connecting up a series of park and rides to connecting places. People are not interested in getting on nowhere and getting off nowhere—they want to arrive at destinations. The renaissance in urban transit has required cross department and cross government relationships. Transport planners have had to think about walking and urban design, while urban planners have had to think about access and mobility. These projects tend to involve different levels of government and partnerships with the private sector. There is a need to collaborate across integrated teams.

The transition to a more sophisticated professional practice to produce highly integrated urban transit planning outcomes has evolved over some time. The change in the way we deliver these projects came out of a need to think differently and more holistically about the delivery of urban transit. There is a need to change the way we deliver parking and at the heart of this is the need to address our professional practice.

Conclusion

One hundred years of urban parking have gutted many cities and damaged our urban places. We have created many urban destinations that are accessible for vehicles but are no longer not worth visiting. This is a liability as cities increasingly measure their success on attracting people/workers and the perception of livability. Many cities are struggling with this, but without the ability to attract skilled workers, they are effectively in economic decline. People want easy access to great cities, places and Main Streets, not just parking.

Parking and its consequences are a complex social, environmental, and economic problem. The discussion here asks that we rethink the professional practice siloes and templates we created many decades ago with their tendency for atomized and specialized work practices to think more creatively about the problem of urban parking. The innovations in parking technologies and policy are heartening, but we need to also radically rethink professional practice to realize parking for great places—attractive, fun, safe, healthy, walkable places that entertain the money out of our pockets.

shutterstock / psynovec, Trong Nguyen, Etien Jones | Unsplash / Scott Webb