The Green Standard

Outlook and Trends for Micromobility

stock.adobe.com / SkyLine

The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) keeps building momentum and grabbing headlines, from the $5 billion investment in EV charging infrastructure announced by the new Joint Office of Energy and Transportation to the marketing pivot by many auto manufacturers toward their growing battery electric and plug-in hybrid lineups. This is great news for cleaner air, climate action, and economic growth.

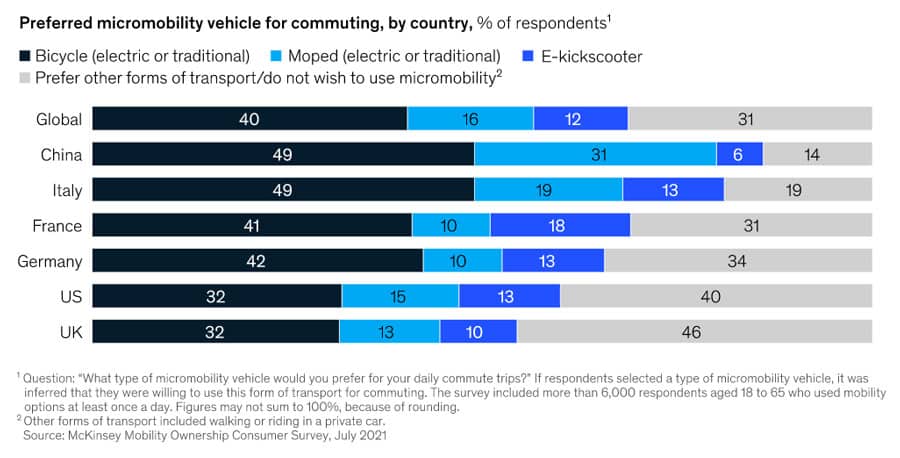

But EVs aren’t the only transportation trend worth watching, a fact underscored by a recent global survey conducted by McKinsey about micromobility preferences for commuting. A somewhat surprising 60% of respondents in the U.S. stated their preference to commute using some form of micromobility. Is it plausible that recent innovations in e-bikes and e-scooters, making them more useful, convenient, and affordable, have caught the public’s imagination? If so, then what will that mean for regulators, parking operators, and future investments in transportation infrastructure? We might find some clues in two innovative approaches featuring micromobility: Pittsburgh’s Move PGH pilot, the most significant demonstration of “mobility as a service” (MaaS) in the U.S., and zero emission areas (ZEAs), a comprehensive policy initiative to address urban congestion and pollution, transportation electrification, and human-centered transportation options (walking, cycling, public transport, and micromobility).

The first dockless electric kick scooters debuted in North America less than five years ago. The common characteristics for micromobility are low speed (under 30 mph), light weight (under 100 lbs.), and partially or fully motorized. A practical classification can be found in Underwriter Laboratories (UL) two certifications related to electrical systems for micromobility: UL 2849 for e-bikes (pedal-assisted or throttle-actuated) and UL 2272 for “e-scooters and other micromobility devices, such as e-skateboards and hoverboards.” While shared-micromobility providers have been a major driver in growing popularity, it’s important to note that micromobility may be personally owned or part of a shared fleet (docked or dockless.)

The smartphone-enabled shared e-scooter concept launched in 2017 quickly migrated beyond the sunny sidewalks of Santa Monica and, before long, venture capital-funded shared-mobility providers emerged in cities and campuses across the U.S. and around the globe. Rapid expansion has often outpaced clear standards for safe operation and respectful use of public space, leading to inevitable controversary. As more communities learn what works, though, they are sharing best practices. The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility and New Urban Mobility Alliance (NUMO)’s Starting Off Right: A Community-First New Mobility Playbook are both excellent resources for communities. Planning for micromobility overlaps with some principles for pedestrian and bicycle planning, and these guides also highlight the considerations specific to e-bikes and e-scooters that lead to more successful outcomes.

The proliferation of shared micromobility services helped showcase how useful e-bikes and e-scooters can be for short urban trips. Public demand for e-bikes is surging. U.S. sales increased 145% from 2019 to 2020 and a proposed 30% tax credit toward e-bike purchases was floated in Congress last year, an acknowledgement that e-bikes are a serious policy option for reducing household transportation costs and vehicle miles traveled (VMT.) Researchers in the UK found high potential for e-bikes to replace some car trips and reduce CO2 emissions, especially in rural areas and places with high economic vulnerability to car dependence. The convergence of public enthusiasm for e-bikes, the emergence of technology-enabled micromobility, and policy priorities sets the stage for local innovation which leads to the first of two notable examples.

Move PGH was launched in July 2021 by the City of Pittsburgh’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) in collaboration with the local transit agency and private-sector partners to deliver a mobility-as-as-service (MaaS) platform for Pennsylvania’s second largest city. MaaS was conceived and first tested in Finland in the early 2010s. The Pittsburgh pilot program is built on the popular Transit smartphone app and, consistent with the MaaS concept, aims to provide a seamless user experience for multimodal trip planning across public and private mobility services. A participant can compare travel options, including public transit and bikeshare, shared-micromobility, carsharing, and carpooling, and purchase trips on any of those services within the app. Micromobility plays a vital role in Move PGH’s value proposition by delivering a “first/last mile” link for public transit and other services, extending access to jobs and other destinations through an integrated regional transportation network. E-scooters were illegal in Pennsylvania until the state passed a special provision allowing Pittsburgh to run the pilot, which opened the door for the shared-micromobility provider Spin to help lead coordination between the many service providers on behalf of the city. “There was an ever-increasing [number of services] but they were siloed and competing for the same customers,” said Lolly Walsh, former director of Move PGH. Working together under the city’s Move PGH initiative, the companies were able to integrate their offerings and remove some of the friction usually associated with accessing multiple transportation options.

Zooming out from Pittsburgh’s pilot, a Zero Emission Area (ZEA) is a policy tool designed and implemented by local governments with the primary purpose of reducing air pollution and carbon emissions from driving. Closely related to congestion zones, which enforce fees upon entry to reduce vehicle travel and congestion, ZEAs instead require vehicles inside their boundaries to meet certain pollution standards. In fact, London’s well-known congestion charge is just one part of a comprehensive zoning scheme that now includes low-emissions zones (LEZs) intended to reduce health impacts caused by pollution from traffic. ZEAs and LEZs are highly flexible and can be designed to meet the specific needs and goals of a community (focusing on delivery vehicles, for example). That flexibility, along with their capacity to evolve over time, make ZEAs an attractive option for cities working toward ambitious goals for climate, electric vehicles, traffic congestion, and public health. C40 Cities, a global network for leading cities taking climate action, cites ZEAs as part of “a coordinated series of strategic actions over the next decade to shift urban mobility choices.”

More widespread implementation of ZEAs could help accelerate the transition to EVs while also promoting micromobility as an attractive option for urban travel. In a report published last December, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) examined scenarios for reducing transportation carbon emissions that align with the goal of keeping below 1.5°C global warming and concluded that the only realistic path follows a dual strategy of rapid electrification alongside policies that focus on shifting travel away from cars. In the context of a projected doubling in passenger vehicles by 2050, the Paris Agreement-aligned scenario includes some sobering targets: phase-out of ICE vehicles globally by 2040 and reduced overall travel demand for driving by 11% compared to business as usual. Meeting these targets will require a transformation in land use and transportation planning. ITDP’s analysis projects that e-bikes are projected to accommodate much of the growth in future vehicle demand and notes that ZEAs are one key approach that can “simultaneously incentivize modal shift and vehicle electrification.” Synergies like this will help ease the transition to future transportation systems that are more shared, electric, and multimodal. Micromobility is positioned at the intersection of those trends, suggesting an even higher profile could lie ahead.

Kurt Steiner, AICP, is associate director, LEED for the U.S. Green Building Council.

-

This author does not have any more posts.